Visitors to the current exhibition at London’s Barbican Centre on the Bauhuas would be forgiven for thinking that the Bauhaus was a style. The exhibition of course contained many beautiful objects in perspex boxes. There was some detailed explanation of the desire to respond to industrial production but there was no reference – apart from a few photographs of empty studios to the fundamental point. The Bauhaus was not a style – it was a school. Jean-Louis Cohen’s The Future of Architecture since 1889 addressed this issue in a fundamental way. He explains that the school rethought the relationship between art, design and architecture. The school championed the new principles of abstract art to challenge existing building forms and then under Hannes Meyer and Mies Van Der Rohe the shapes of cities.

The Bauhaus Cohen explains, marks a fundamental shift in teaching. Whilst the school produced great works of art, its whole purpose was towards architecture. In Gropius’s founding program he described the goal of the new school: “to bring together all creative efforts into one whole to reunify all the disciplines of practical art – sculpture painting handicrafts and the crafts which are inseparable components of a new architecture.” He added: “The ultimate if distant aim of the BAuhaus is the unified work of art – the great building in which there is no distinction between monumental and decorative art.” Architecture was not taught until 1927. Yet despite this departments were organised as a series rather than as a hierarchy. Departments, literally had open doors between them at the Dessau campus.

Today we view design schools relationship with the outside world in one direction. What kind of designers should these schools produce? Should they be ready to design industrial products? Or should they emerge as questioning individuals. In its own terms the BeOpen Inside The Academy Prize is a great way to further invigorate a winning institution’s curriculum by granting it the opportunity to select and host a series of talks by guest lecturers. It is a prize that helps director’s of institutions and heads of schools to create their dream institution. It also provides a timely of considering how cultures help form design schools rather than the other way around. And how success in design schools is often determined by a confluence of unique teachers address the particular culture of a design school.

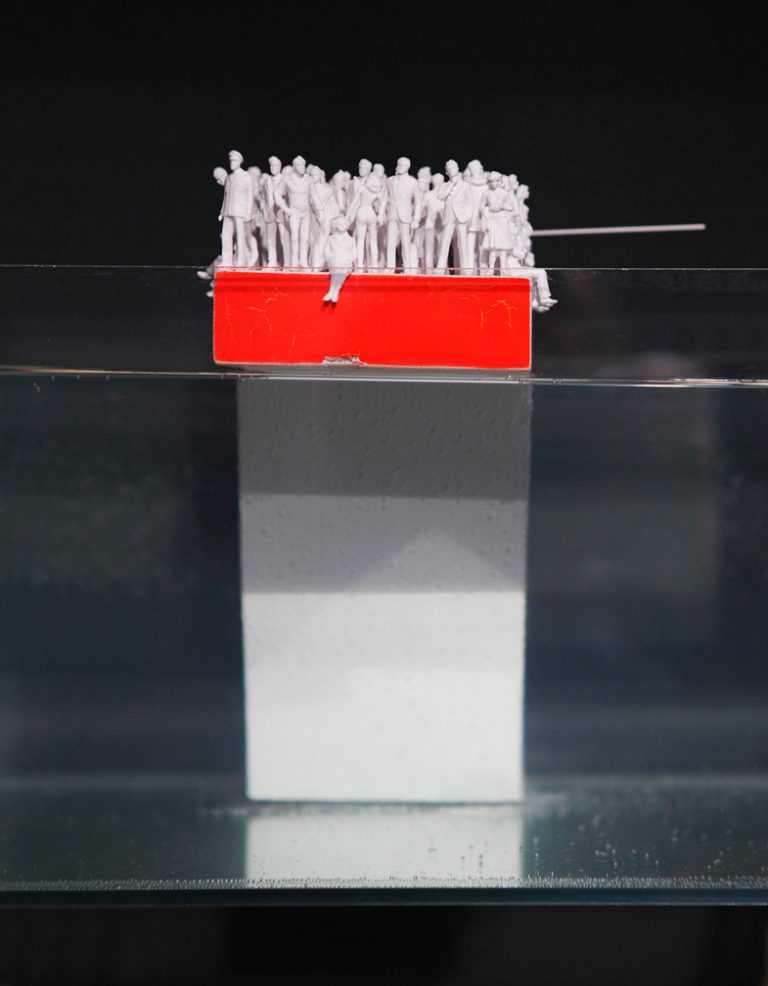

Jurgen Bey has had a singular insight into the best of European design academe. He studied for 5 years at the Design Academy in Eindhoven and then taught their for another six years. He was Professor of Design at Hochschule fur Bildende Kunsten in Karlsruhe and then taught at the Royal College of Art briefly. Within that varied experience he has explored consistently the relationship between art and design practices. It is no surprise that he has found a perfect place at the Sandberg Institute. “It’s a rather small school, but in reality The Sandberg institute is the masters course of the Rietveld Academy, which is a school for art. At Sandberg I feel that our backbone is art, then we have all these applied departments.” One of the student projects from Sandberg on show in Basel was a proposal for a floating forest; whimsical perhaps but beautiful. Showing the power of the unfettered imagination though, this proposal has already attracted the attention of Rotterdam city authorities with an idea to execute it.

To match the clear vision of the school’s position, Bey has a very clear vision of what makes studying design special and what makes it so useful in an era of economic and moral uncertainty. “If you don’t know where you are heading then it is really good to raise questions and start debating. [Recently] our language has changed and we are not debating any more, we’re just saying how things should be, but I think the debate is more important than the actual happening. You are able to debate what you stand for, but at some point you are able to say, this is not my point, but yes you are right. Politics is all about being right, economics is all about being right, and beauty is not about being right.’ Thus the project they contributed to the competition in which a Morrocan woman sings the Dutch national in Arabic is a means of questioning a huge range of ideas without being overtly polemic.

Yet this ability to think coherently about the present and the future is built on strong historic foundations. The Rietveld Academy was originally the Applied Art Academy formed in 1924 from 3 other schools and set up in a similar way to the Bauhaus. As a school it provided the perfect platform for the designer. Technical skills were taught within small studios of similar sizes throughout a relatively small institutions. Students had to take courses in completely different media from that which they studied. Rather than focusing on the craft of the technique though, teaching praised artistic independence as well as creating something social useful. Another shortlisted school for the competition, La Cambre was created at the end of the 20s by Henry Van de Velde opened La Cambre with the same philosphy of the Bauhaus – championing the individuality of the artist, albeit for them to make use of standard simple building types and materials.

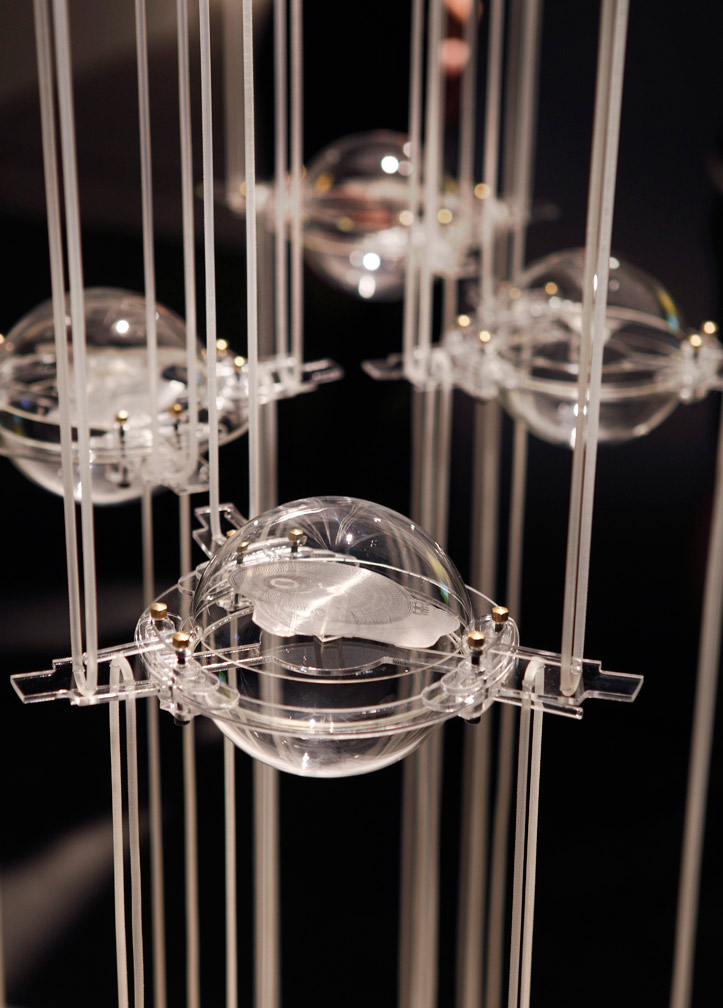

Jean Pierro Pitischi is responsible for Masters 2 programme at the Belgian school and compares it to the mother of all design schools. “La Cambre is still very close to that philosophy, particularly the fact that we are sharing the school with 17 other departments from sculpture to paintings to ceramics. It’s quite unusual in Europe I think. Each department is equal in the Bauhaus manner. It takes three years batchelor and 2 years master. You gain a qualification as a batchelor of industrail design. Every student must go twice for a period of 6 weeks in another a department just to try things out with another discipline.” One of the pieces of students work they exhibited at Basel was actually a toy for teaching children angles using coloured metal bars. It even looked like a Bauhaus design.

The way that the Bauhaus established a system to engender unique skills to visualise and create responses to problems. Other schools in the shortlist for the In The Academy Award, have engendered a more problem based approach. Rather than concentrating on producing a technique and an enquiring mind, they ask students to solve, what are apparently real-life problems. Although he is a tutor on the Product Design course, Stuart Bailey is an advocate of service design: the contentious idea that designers can intervene in bureaucratic structures, nominally through the creation of information technology systems but more generally to improve them using design skills. This course doesn’t provide the student with time to thin apart from the world, but puts them instantly on the track to creating something socially useful, although the exact terms of what is socially useful have already been determined for them.

Although it was pioneered in Koln, Glasgow is a leading light in this field in the UK. As Bailey explains it, “Our head of department is a social scientist. Dr Gordon Hush. He studied sociology at the University of Glasgow up to Phd level and trained as a social scientist. He formalised a lot of social science into [the course] although the teachers have all got a multiple range of backgrounds. “ At Konstfack too the emphasis is not on traditional design skills. Indeed the attempt to transcend disciplines is almost eroding the idea of a discipline at all. Ronald Jones, who heads the Masters in Fine Art at the Experience design group says, “Designers are not good at making stuff, they are good at transforming people’s lives. Sometimes through stuff.”

The Inside The Academy competition prioritises the relationship between culture and academia in a more positive way. Rather than asking what design students contribute to a wider culture the competition says, what can a wider culture contribute to a design school. Bey’s dream ticket would be to bring the maverick artist Francis Alys to the Sandberg Institute – an artist who has more than any other of his contemporaries, examined the relationship between man and what he calls his environment. It is hard to think of anyone better to bring into a design school.